Understanding the Risk vs. Reward of Department of Justice’s Corporate Criminal Whistleblower Awards Pilot

The Securities & Exchange Commission, the Department of Health & Human Services, and other agencies have long had established bounty programs that reward successful tipsters. On August 1, 2024, the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Criminal Division joined these other agencies, launching a three-year Corporate Whistleblower Awards Pilot Program (the “Pilot Program”). The Pilot Program marks a significant effort by DOJ to enhance its ability to fight corporate crime by enlisting whistleblowers to aid in the effort. While there is some skepticism as to the Pilot Program’s potential success, there is no doubt it presents new challenges for companies. This article provides an overview of the Pilot Program as well as guidance for companies subject to its framework.

Overview of Program

The Pilot Program provides a bounty for successful tips relating to “possible violations of law” for four categories of crimes: (1) foreign corruption and bribery; (2) financial institution crimes; (3) domestic corporate corruption; and (4) health care fraud involving private insurance plans. DOJ press focuses on these four areas, though the intake form provides a fifth “other” option for a reporter to select.

Eligibility & Key Terms

To be eligible, whistleblowers must provide original, non-public, and truthful information of a possible violation of law that leads to a successful forfeiture exceeding $1 million. Legal, audit, and compliance personnel are presumptively ineligible, and reporters who “meaningfully participated” in the reported criminal activity are not eligible for an award under the Pilot Program.

DOJ has not defined what it considers meaningful participation. However, Pilot Program guidance provides that an individual who was “directing, planning, initiating, or knowingly profiting from” the criminal conducted reported is not eligible. Further, Footnote 4 of the guidance provides “an individual remains eligible for an award under the [] Pilot Program if the Department determines, in its discretion, that the individual’s minimal role in the reported scheme was sufficiently limited that the individual could be described as ‘plainly among the least culpable of those involved in the conduct of a group.’” These terms parrot similar mitigation principles in the Sentencing Guidelines and suggest the phrase “meaningfully participated” requires a significant involvement or at least more than a minimal role in the reported criminal conduct.

Information provided by whistleblowers also must be original, i.e., based on the individual’s independent knowledge and not already known by DOJ. Information obtained through a privileged communication is also excluded from DOJ consideration (according to Pilot Program terms).

All whistleblower reports must be truthful and complete as well as include all the information of which they have knowledge, including any misconduct they may have participated in. DOJ further has made it clear that if a whistleblower withholds information or misrepresents his potential involvement in misconduct, he is ineligible for a Pilot Program award. Full and truthful information includes full cooperation with DOJ in any investigation, including providing truthful testimony during interviews, before a grand jury, and at trial or any other court proceedings, and they must produce all documents, records, and other relevant evidence.

Award Structure

If eligible, a whistleblower may be entitled to a discretionary award of up to 30% of the first $100 million in net proceeds forfeited and up to 5% of the next $100 million to $500 million in net proceeds forfeited (notably, not net proceeds lost). DOJ has made it clear any award is fully discretionary, and in determining whether a whistleblower will receive an award, it will consider if the information provided was specific, credible, and timely, and also whether the information significantly contributed to forfeiture. The DOJ also will assess the whistleblower’s level of assistance and cooperation throughout the investigation.

The Pilot Program is the first of its kind to cap awards and also to require any award be paid from net proceeds forfeited. Under relevant criminal forfeiture statutes, proceeds are forfeitable only if they are derived from or substantially involved in commission of an offense. In this way, net proceeds forfeited may be less than actual loss. (In a contrasting example, Dodd-Frank Act (“Dodd-Frank”) whistleblowers are guaranteed an award between 10-30% of collected funds so long as the whistleblower is not convicted. Additionally, Dodd-Frank provides for judicial review of award determinations.)

Corporate Self-Disclosure

The Pilot Program does give companies a 120-day window to self-disclose information related to an internal whistleblower report. Companies choosing to self-disclose “misconduct” conduct covered by the Pilot Program within the allotted 120-day window will remain eligible for a presumption of declination (i.e., no prosecution) under the Corporate Enforcement and Voluntary Self-Disclosure Policy (the “Self-Disclosure Policy”). This 120-day window applies even if the whistleblower has already reported misconduct to DOJ.

Companies choosing to self-disclose also must meet the other requirements of the Self-Disclosure Policy to qualify for a presumption of declination. In addition to a timely self-disclosure, companies must cooperate fully with the investigation, identify responsible individuals, remediate all harms, and disgorge ill-gotten gains.

Impact on Investigations

The most immediate impact on companies is likely on the pace and structure of internal investigations due to the condensed 120-day timeline DOJ has announced — especially when a whistleblower reports suspicions internally, and a company could thereafter be eligible for a presumption of declination under the Self-Disclosure Policy. This condensed timeline may put pressure on companies to rush through internal investigations, in notable contrast to a meaningful investigation contemplated by Chapter 8 of the Sentencing Guidelines.

Pace of Internal Investigations

The 120-day window to self-disclose may create pressure to make hasty decisions after incomplete or rushed internal investigations, especially since DOJ is prepared to accept reports of “misconduct” and does not require a probable violation of criminal laws. At minimum, companies should ensure they have strong and robust internal reporting structures for misconduct (whether or not criminal) and are prepared to promptly investigate any reported alleged misconduct. Again in contrast to Dodd-Frank, where there is no specific time frame in which a corporation must self-disclose criminal conduct, the 120-day period is short, especially when considering the amount of time, effort, and resources appropriately dedicated to determining whether a crime actually was committed. It is possible DOJ is counting on companies to prematurely report leads for DOJ to investigate, before companies can make their own mitigating determinations about intent, scope, criminality and remediation.

Notably, the 120-day disclosure period is different than the Self-Disclosure Policy’s requirements for timely reporting. For M&A due diligence reporting, which is the only circumstance in which there was previously an identifiable deadline, if an acquiring entity discloses misconduct uncovered through due diligence, it must “timely disclose[] to the Department . . . , which generally means within 180 days of the closing date of the transaction.” For all other disclosures, the policy requires companies to “disclose[] the conduct to the Criminal Division within a reasonable time after becoming aware of the misconduct, with the burden being on the company to demonstrate timeliness.” If certain enumerated “aggravating circumstances” are present, there is no presumption of a declination, but the government still may consider a declination if the company reports on a sped-up timeline — i.e., “immediately upon the company becoming aware of the allegation of misconduct.” Therefore, the new deadline to self-disclose is stricter than the current baseline in the Self-Disclosure Policy, leaving companies with only four months after an internal whistleblower report to determine whether allegations amount to actual reportable criminal activity.

The Pilot Program also undermines internal investigations by incentivizing companies to disclose “misconduct” and not merely criminal conduct — the former being easier to identify. By disincentivizing companies from engaging in a more thorough and thoughtful investigation before deciding whether to disclose, the government risks beginning its own investigation without the benefit of context or full information or negotiating a resolution following a presentation of internal investigation findings. The Self-Disclosure Policy already accounted for this issue; the Pilot Program shortens the time for a thoughtful and thorough investigation.

The Sentencing Guidelines also already incentivize companies to move swiftly to address reported misconduct, providing for a reduction of culpability score when companies report an offense within “a reasonably prompt time after becoming aware of the offense.” The Guidelines notes further explain “the organization will be allowed a reasonable period of time to conduct an internal investigation” to qualify. Disclosing criminal activity is an act companies take seriously, as reporting often causes significant collateral consequences. To expect companies to report misconduct before they have thoroughly investigated an allegation may not effectively serve the government’s goals of strengthening corporate accountability.

Potential Privilege Concerns

Companies also should be concerned about being able to conduct a privileged internal investigation, since interviewees may make assumptions based on communications with counsel or use information learned in an investigation in a report to the government. The Pilot Program contains two provisions that appear to attempt to protect privileged communications before disclosure, both of which fall under the requirement that information reported to the Criminal Division be “original.”

First, information is not “original” if the whistleblower “obtained the information through a communication that was subject to the attorney-client privilege[.]”

The second provision is less straightforward. Here, information is not original if the whistleblower obtained the information because they were:

- an officer, director, trustee, or partner of an entity and another person informed them of allegations of misconduct, or they learned the information in connection with the entity’s process for identifying, reporting, and addressing possible violations of law;

- an employee whose principal duties involve compliance or internal audit responsibilities, or they were employed by or otherwise associated with a firm retained to perform compliance or internal audit functions for an entity, and the information relates to or is derived from these responsibilities or functions;

- employed by or otherwise associated with a firm retained to conduct an inquiry or investigation into possible violations of law and the information relates to or derives from that retention; or

- an employee of, or other person associated with, a public accounting firm.

The first two of these exclusions may protect a company’s internal investigations to some extent, but it is limited to higher-level employees — officers, directors, partners, etc. — and employees engaged in compliance or audit functions. These exceptions would not protect communications in the course of an investigation with lower-level employees who are not in a compliance or audit role.

There also are several exceptions to these exclusions based on original information, including if the whistleblower:

- has a reasonable basis to believe that disclosure of the information to the Department is necessary to prevent the relevant individual or entity from engaging in criminal conduct that is likely to harm national security, result in crimes of violence, result in imminent harm to patients in connection with health care, or cause imminent financial or physical harm to others;

- has a reasonable basis to believe that the relevant individual or entity is engaging in conduct that will impede an investigation of the misconduct; or

- is someone described in [Subsection] (iv)(a) or (iv)(b) and at least 120 days have elapsed since they provided the information to the relevant entity’s audit committee, chief legal officer, chief compliance officer (or their equivalents), or their supervisor or, since they received the information, if they received it under circumstances indicating that the entity’s audit committee, chief legal officer, chief compliance officer (or their equivalents), or their supervisor was already aware of the information.

Subsections (a) and (b) provide broad exceptions, requiring only that the whistleblower have a “reasonable basis to believe” that reporting is necessary to prevent enumerated potential harm or that the company would impede an investigation. There also is no clear definition of what constitutes “imminent harm to patients” or “imminent financial or physical harm” and whether it is the Department or the whistleblower’s subjective belief about the imminency of harm that controls whether the report is excluded as original. Subsection (c) also places additional time pressure on a company once an employee discloses misconduct to an audit committee or chief legal officer, given the 120-day reporting period. Companies should be aware of this 120-day period as well when proceeding with an investigation.

Given these broad exceptions as well as the critical need for companies to obtain meaningful advice from counsel, investigating attorneys will need to carefully prepare for a potential disclosure of privileged information. Companies should take caution and great care to preserve privilege when conducting an internal investigation, as whistleblowers could be investigation witnesses. It now is more important than ever for counsel to explicitly record when employees are acting — e.g., gathering information or creating summaries — at the instruction of an attorney for the purpose of obtaining legal advice for the company and instruct employees in witness interviews that the company is working with counsel and needs counsel’s advice before acting. This includes:

- Counsel leading the team. In-house or outside counsel should lead the investigation team and ultimately guide the investigation.

- Putting the Investigation Mandate in Writing. This document should contain instructions for the internal investigation, define its scope, and confirm the purpose of obtaining counsel’s advice. Not only will this assist in preserving privilege, but it will provide focused guidelines necessary for a fast-paced investigation.

- Limiting Non-Attorney Involvement. Limit non-attorney involvement in the investigation as much as possible. This may mean engaging third-party experts such as forensic accountants instead of relying on the company’s own personnel to evaluate the company’s records. When retaining such experts, document that the expert has been retained to assist counsel in providing legal advice and services.

- Distinguish Between and Among Legal Advice, Employment Counseling, and Business Recommendations. The law governing privilege scope is evolving, and employment or business advice typically is not privileged. Keep privileged communications separate.

Delay in Government Investigations

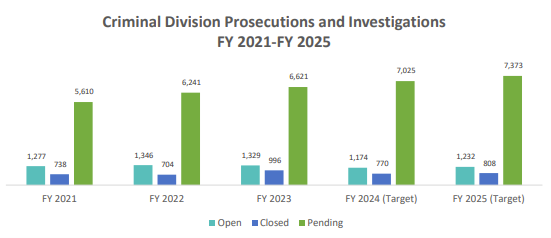

The DOJ Money Laundering and Asset Recovery Section (MLARS, the group responsible for forfeiting proceeds from or involved in crimes) also now has a heightened role in corporate criminal matters. If the Pilot Program follows the trend of other whistleblower programs, MLARS will be looking at a significant increase in tips. For example, the SEC whistleblower program, which was established in 2010, received more than 18,000 whistleblower tips in 2023, up from 12,300 tips in 2022 and 12,200 in 2021.[1] Should this upward trend be reflected in the Criminal Division program, it will likely be a challenge for MLARS to keep up with the number of tips and ongoing investigations. The Criminal Division is already busy; in its 2025 Budget Narrative, released in March 2024, the department demonstrated that, for 2024, it expects to have 1,174 open investigations and over 7,000 pending investigations:

Chart: FY 2025 Budget Narrative, at 4.

In the midst of this heavy caseload, the government “has recently faced significant challenges in [its workforce] that affect recruitment, employee retention, and diversity,” including the inability to offer competitive pay with the private sector or other government agencies.[2] While the Criminal Division sought to increase its staffing by almost 100 people in connection with the Pilot Program, 65 of which would be attorneys, only 26 of those positions (14 attorneys) would be allocated to the Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section and MLARS, with a focus on “enhancing cybersecurity and fighting cybercrime.”[3] This is likely to add only minimal relief to the current staffing constraints and caseloads, let alone to any influx of cases based on new whistleblower tips.

Because one of the Pilot Program’s focuses is on foreign corruption, e.g., FCPA, FEPA, and money-laundering cases, the government is likely looking at increased burden here on investigation resources. Often these cases are complex and involve multiple (and international) jurisdictions. The Criminal Division stated in its FY2025 Budget Narrative:

Global crime investigations and prosecutions typically requires significant resources, including expert witnesses and investigators; coordination and communication across the Department, the federal government, and foreign countries; and specialized technology.[4]

These resources will be especially pressed given the resource-intensive cases the Pilot Program will likely attract.

Financial Impact to Companies

Although companies should not underestimate the potential impact of the Pilot Program on internal investigations, there are several meaningful factors that may limit the applicability and financial effect.

Recovery Is Based in Civil, Criminal, or Administrative Forfeiture

Authority for the pilot program is grounded in the Attorney General’s ability to use the Assets Forfeiture Fund to pay awards for “information or assistance leading to civil or criminal forfeiture.” 28 U.S.C. § 524(c)(1)(C). This is distinct from other forms of monetary recovery, such as restitution, administrative forfeiture, or civil or criminal penalties. For the government to have authority to recover under the Pilot Program, then, the crime must provide for forfeiture.

It may seem a mere procedural issue, but the availability of forfeiture is more limited than the availability of damages or penalties. Criminal forfeiture is an action against an individual that includes notice of the intent to forfeit property involved or derived from the particular counts on which a defendant is convicted.[5] Civil forfeiture is a proceeding brought “against property that was derived from or used to commit an offense,” where the defendant is the property itself. Administrative forfeiture, though similar to civil forfeiture, involves a proceeding before the agency that seized the assets instead of a proceeding in federal court.

While a more restricted avenue of recovery, the government has obtained some substantial recoveries through forfeiture in the FCPA and anti-money laundering space in particular, including several in the past year. For example, the forfeiture statutes clearly allow for forfeiture in money laundering cases, and DOJ has in recent years begun to impose gain-based criminal forfeiture on top of criminal fines in FCPA cases. In late 2023, Gunvor, one of the world’s largest oil traders, pleaded guilty in its foreign bribery case, agreeing to forfeiture of its ill-gotten gains constituting more than $287 million — almost half of the over $600 million in criminal penalties.[6] Earlier in 2024, a father and son were sentenced in a money laundering case to forfeit all bitcoin seized by the government, which had an estimated value of somewhere between $65 million and $150 million.[7] These both pale in comparison to the November 2023 Binance resolution in which Binance agreed to forfeit approximately $2.5 billion on top of its $1.8 billion criminal fine for money laundering and sanctions violations.[8] Even if forfeiture is not always part of a recovery, these big numbers still may be an enticing prospect for would-be whistleblowers.

There is a possibility the advent of the new whistleblower program will lead to lobbying for legislation to expand DOJ’s authority to share its recovery beyond forfeiture, as it unsubtly alluded to in its fact sheet. Whistleblower attorneys — who certainly stand to benefit from a whistleblower’s access to more than just forfeiture funds — may take this opportunity to push for a share of restitution or agency losses, to reap rewards beyond a share of forfeiture.

There Is No Floor for Recovery to Whistleblowers

The incentive to prospective whistleblowers to make a report pursuant to the program on the other hand may be curbed because there is no guaranteed monetary recovery under the Pilot Program. Awards are fully discretionary, not subject to appeal or floor, and are capped. Moreover, the Pilot Program carries significantly more risk for whistleblowers than other established programs. For example, the False Claims Act requires a minimum reward of 15% of all collected funds, and the SEC Whistleblower Program sets a floor of 10%. These programs have been significant sources of funds for both the government and whistleblowers, with the SEC’s program awarding over $600 million to whistleblowers in 2023, and the FCA’s program resulting in $2.3 billion in settlements and judgments for that same period, of which tipsters recovered 15 to 30%.

Potential whistleblowers still may be incentivized by the possibility of recovering millions of dollars under the program, notwithstanding retaliation risk, blacklisting, and unwanted publicity. Whistleblowing also requires significant time and attention. Individuals who decide to make these reports under other programs are nearly guaranteed a payday, as even investigations that may not ultimately succeed at a trial often result in a monetary settlement of which the whistleblower receives a cut. Under the Pilot Program, however, there is a non-negligible chance that a whistleblower could ultimately receive nothing, even where the claim was meritorious and leads to government recovery. For this reason, potential whistleblowers may choose not to take the risk.

Little Impact on Companies with Pre-existing Self-Disclosure Requirements

Companies with pre-existing self-disclosure requirements may not experience significant effects from the Pilot Program. For example, Department of Health and Human Service contractors and grant recipients already are required to disclose evidence of potential violations of federal criminal law involving fraud, bribery, or gratuity violations.[9] Most government contracting programs, such as those with the Department of Defense or Department of Commerce, contain similar requirements under Federal Acquisition Rule 52.203-13, which remain in place until at least three years after final payment on a contract.[10] Additionally, some companies may have a Corporate Integrity Agreement in place with the Office of Inspector General following settlement of a False Claims Act case, which almost always requires them to report any “matter that a reasonable person would consider a potential violation of criminal, civil, or administrative laws applicable to any Federal health care program for which penalties or exclusion may be authorized.”[11] Whistleblowers coming forward in these contexts may not be viewed as coming forward voluntarily (an argument companies likely will make).

While the full impact of the Pilot Program remains to be seen, what is already clear is that companies should be prepared to move efficiently following a credible internal tip. By proactively bolstering internal reporting systems and response times, particularly for reports related to money laundering, fraud, corruption, and bribery, companies can more smoothly adapt to the Pilot Program’s impacts. Foley has the resources to help you navigate the complexities of a changing self-disclosure environment. Please reach out to the authors, your Foley relationship partner, or to our Government Enforcement Defense & Investigations Practice Group with any questions.

[1] U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, SEC Whistleblower Office Annual report FY 2023, at 1 (Nov. 14, 2023) https://www.sec.gov/files/fy23-annual-report.pdf; U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, SEC Whistleblower Office Annual report FY 2022 at 1, (Nov. 15, 2022) https://www.sec.gov/files/2022_ow_ar.pdf; U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, SEC Whistleblower Office Annual report FY 2021 at 28, (Nov. 15, 2021) https://www.sec.gov/files/owb-2021-annual-report.pdf

[2] FY 2025 Criminal Division President’s Budget Narrative (“Budget Narrative”), https://www.justice.gov/d9/2024-03/crm_fy_2025_pb_narrative_-_final_03.05.24_1.pdf.

[3] FY 2024 Criminal Division Budget Performance Summary, https://www.justice.gov/d9/2023-03/crm_fy_24_budsum_ii_omb_cleared_03.08.23.pdf.

[4] Budget Narrative at 13.

[5]U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Types of Federal Forfeiture, https://www.justice.gov/afp/types-federal-forfeiture#:~:text=Civil%20forfeiture%20allows%20the%20government,located%20outside%20the%20United%20States.

[6] See Press Release, U.S. Attorney’s Office for Eastern Dist. of N.Y., Gunvor S.A. Pleads Guilty to Scheme to Bribe Ecuadorian Officials and Ordered to Pay Over $600 Million in Criminal Penalties (Mar. 1, 2024), https://www.justice.gov/usao-edny/pr/gunvor-sa-pleads-guilty-scheme-bribe-ecuadorian-officials-and-ordered-pay-over-600.

[7] See Press Release, U.S. Attorney’s Office for Dist. of Md., Father and Son Sentenced for Laundering Drug Trafficking Bitcoin Proceeds Intended for Federal Forfeiture (Jan. 8, 2024), https://www.justice.gov/usao-md/pr/father-and-son-sentenced-laundering-drug-trafficking-bitcoin-proceeds-intended-federal.

[8] See Press Release, Office of Public Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Binance and CEO Plead Guilty to Federal Charges in $4B Resolution (Nov. 21, 2023), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/binance-and-ceo-plead-guilty-federal-charges-4b-resolution.

[9] See U.S. Office of Inspector General, Self-Disclosure Information, https://oig.hhs.gov/compliance/self-disclosure-info/; U.S. Office of Inspector General, Contractor Self-Disclosure FAQs, https://oig.hhs.gov/faqs/contractor-self-disclosure-faqs/.

[10] See Office of Inspector General, FAR Disclosure Requirements, https://www.oig.doc.gov/Documents/FAR-disclosure.pdf.

[11] See Office of Inspector General, Corporate Integrity Agreement FAQs, https://oig.hhs.gov/faqs/corporate-integrity-agreement-faq/.