Delaying Examination of Continuing Applications Could Sabotage USPTO Goals

Rumor has it that one of many behind-the-scenes changes being implemented at the USPTO relates to how (or when) continuing applications are taken up for examination. Typically, an examiner may give priority to a continuing application based on its U.S. priority date. That could change, with placement in the examination queue being based on the actual filing date of the continuing application itself. This effort to move continuing applications to the back of the line may be spurred by a narrative that continuation applications are a burden on the USPTO and hindrance to competition, but its implementation could sabotage important USPTO’s goals.

Loss of Examination Efficiency

One reason an examiner may choose to give priority to a continuing application is an expectation that it will be relatively easy to examine. The examiner is already familiar with the technology and the prior art, and so can immediately focus on evaluating patentability of the claims. Moving continuing applications to the end of the examination queue would lose these efficiencies. The current average time to examination is over 20 months and climbing. With a two year gap between examination of a parent application and its child, it is likely the examiner will have to spend more time getting reoriented to the subject matter of the application and its place in the state of the art.

Loss of Maintenance Fee Revenue

A more concrete impact of de-prioritizing examination of continuing applications is the consequent loss of maintenance fee revenue. The current USPTO fee schedule includes a new surcharge for continuing applications filed “late” in their 20-year term that is designed to “partially offset foregone maintenance fee revenue.” The USPTO justified the new fee by explaining that maintenance fee payments are essential to the USPTO’s fiscal health, “account for about half of all patent fee collections,” and “subsidize the cost of filing, search, and examination activities.” So, why would it implement internal changes that will leave more maintenance fees on the table?

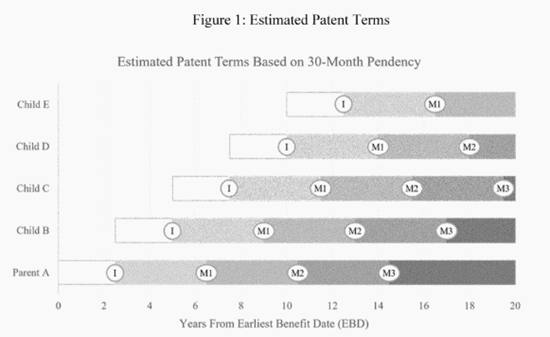

Maintenance fees are due 3.5, 7.5 and 11.5 years after a patent grants, but a patent’s potential term is measured from its earliest non-provisional U.S. priority date. This means a patent granted more than 8 years after its priority date may expire before one or more maintenance fees must be paid (as illustrated in the USPTO’s figure below). But this also means the USPTO has incentive to expedite the examination and grant of continuing applications.

This figure assumes a continuing application will be granted 30 months from its actual filing date, but also illustrates how delays in grant can cause one or more maintenance fee deadlines to fall off the chart and not be paid.

Take a continuing application filed just after 6 years from the start of its 20-year term (between Child C and Child D in the figure) and subject to a new surcharge of $2700. If this application is granted after 30 months (2.5 years), its 20-year term will expire just as the third maintenance fee would be due (M3 in the figure), so that fee will not be paid. On the other hand, if the patent is granted within 1.5 years, it is at least possible the patent owner would want to maintain it for another year—and probable if it is protecting an approved pharmaceutical product. At current maintenance fee rates, that means the USPTO is potentially losing $8,280 per application by not striving to expedite examination and grant of continuing applications subject to the $2700 surcharge.

A continuing application filed just after 9 years from the start of its 20-year term (between Child D and Child E in the figure) and subject to a new surcharge of $4000 is never going to pay the last maintenance fee, but the sooner the patent is granted, the more likely the patent owner will want to pay the second maintenance fee (M2 in the figure), which currently is $4040. If it takes 30 months to grant, the second maintenance fee will be due one year before expiration of the 20-year term, but if it takes only 18 months to grant, there will be two years left when the second maintenance fee falls due. That means by expediting examination and grant of continuing applications subject to the $4000 surcharge the USPTO could double the incentive to pay the $4000 maintenance fee.

Data-Driven Decision Making

In this era of data-driven decision making, the USPTO should be able to mine its examination metrics to confirm that prompt examination of continuing applications supports an efficient examination process, and it should be even more straight-forward to mine maintenance fee payment metrics to estimate the additional maintenance fee revenue that could be generated by prioritizing examination and grant of continuing applications. When crunching the numbers, the USPTO should take into account that patent owners willing to pay the new surcharges already place a high value on these applications, and so may be more likely to pay maintenance fees that fall due toward the end of the patent’s 20-year term.

If the data indicate that putting continuing applications at the back of the line undermines USPTO examination goals and exacerbates loss of maintenance fee revenue, the USPTO should revoke its decision to de-prioritize examination of continuing applications. In the meantime, stakeholders should be aware of the USPTO’s negative view of continuing applications, and look for opportunities to rebut the narrative that continuing applications are less deserving of the USPTO’s examination resources than so-called “new” applications.