Companies often enter into supply agreements for component parts that are covered by or produced using a supplier’s intellectual property (IP) rights, but do not give enough thought to IP licensing. In the face of supply chain disruptions and the associated need to investigate second-sourcing and in-housing options, suppliers may be keen to capitalize on those rights to prevent such production of their proprietary parts. For example, the supplier may assert that the component part is covered by a patent or that second-sourcing or in-housing by the customer would use the supplier’s “know-how.” As a result, supplier’s IP rights, usually an afterthought in the context of ordinary supply arrangements, have now been thrust to the forefront of consideration in many industries.

Especially during and as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, unexpected supply chain disruptions and delays have arisen, preventing certain suppliers from being able to provide components or materials to customers in a timely manner, the required quantity, or at an agreed-upon price. In some cases, the disruptions substantially impede the customer’s own ability to deliver its products on time, on budget, and in sufficient quantities, causing loss of revenue and customer goodwill.

In order to address these supply chain risks, customers should negotiate, as part of the supply agreement or even as a stand-alone document, the ability to utilize their supplier’s IP in certain instances where the supplier claims it cannot provide the requisite quantity of the subject component in a timely manner or at an agreed-upon price. Whether through outsourcing the component manufacture to a third party or by in-housing the production, a customer should give itself the option to use the supplier’s IP so that there is as little disruption in production as possible. The customer can secure this option through negotiations with the supplier to establish, for example, a conditional license or an intellectual property escrow that permits the customer to utilize the supplier’s IP in the event of certain, agreed-upon conditions.

Patents and Know-How Common in the Supply Chain

A supplier may have various IP rights covering a component that it supplies to a customer, including patent rights and rights protecting the supplier’s “know-how.” Generally, a patent provides the patentee (the supplier, in this instance) with the exclusive right to prevent others (a customer, third parties hired by the customer, or anyone else) from making, using, selling, offering to sell, or importing the product covered by the patent, absent any agreement to the contrary. Whether or not the component is patented, the supplier may also have an interest in protecting its know-how with respect to the component. Know-how can be tangible or intangible, may or may not be patentable, and may or may not be protectable via state-law trade secret statutes.1 Know-how can include, for example: scientific or technical information, results, and data of any type; trade secrets; practices, protocols, methods, processes (including manufacturing processes), or techniques; component specifications (e.g., dimensions, material selection, bill of materials (BOM), etc.); and engineering drawings and three-dimensional computer-aided-design (CAD) models. A supplier may attempt to withhold from sharing and maintain as secret much of its know-how in a component. But in some instances the supplier may need to share at least some of its know-how with its customer so that the customer can design and produce the end product, such that the component can be integrated as part of the assembly, to generate product drawings and models for production and assembly instruction purposes, etc.

Dilemma: Typical IP Provisions Included in Supply Agreements

Supply agreements typically treat IP as an afterthought, for example when they define the IP rights of the supplier and include only a limited right for the customer to use that IP. Traditional supply agreements may also define and include only a limited right to use the supplier’s know-how (e.g., the know-how that is shared with the customer may be used only for specific, enumerated purposes by the customer, the know-how that is shared with the customer may not be widely disseminated, etc.). However, should a disruption in the supply chain or delay in the delivery of the components arise under traditional supply agreements, the customer may face a lose-lose situation: (a) lose revenue and customer goodwill by being unable to meet product demands or (b) run afoul of the supplier’s IP rights by having the component manufactured outside of the bounds of the supply agreement.

Answer: Include Conditional License to Patents and Related IP in Supply Agreements

While IP terms in supply agreements were historically limited and sporadic, the current supply environment demands that customers take supplier IP seriously. Supply agreements should include various supplier representations and warranties regarding whether the component being supplied is patented. The supply agreement may also require a covenant that the supplier will notify the customer if anything about the patented status of the component changes throughout the term of the supply agreement (e.g., a patent expires, a new patent issues that covers the component, new patented features are introduced to future generations of the component, etc.). Similarly, provisions for know-how, confidential information, copyrights, and trade secrets should be included, such as a supplier acknowledgement that information is not confidential or know-how unless marked by the supplier as such. These provisions are intended to promote certainty by preventing the circumstance where the customer later wants to second-source the component part but is frustrated to find out a supplier’s IP rights will prevent it from doing so.

Knowing about a supplier’s patent(s) or other IP is only half of the solution – to avoid disruption, customers should make every attempt to negotiate an upfront, conditional license with the supplier that outlines when the customer may, under certain conditions, either manufacture the component itself (in-housing) or have the component manufactured by a third party (second-sourcing). This typically will come in the form of a license that allows the customer to produce the component without infringing upon the supplier’s patent rights or misusing the supplier’s know-how. The license may also allow for the use of the supplier’s drawings, avoiding the cost associated with redrawing components later on. Such a license will allow the supplier and the customer to specify clearly when the conditional license activates, for how long, and what information the customer may use so that the customer can act quickly and mitigate any adverse impacts on the manufacturing of their product.

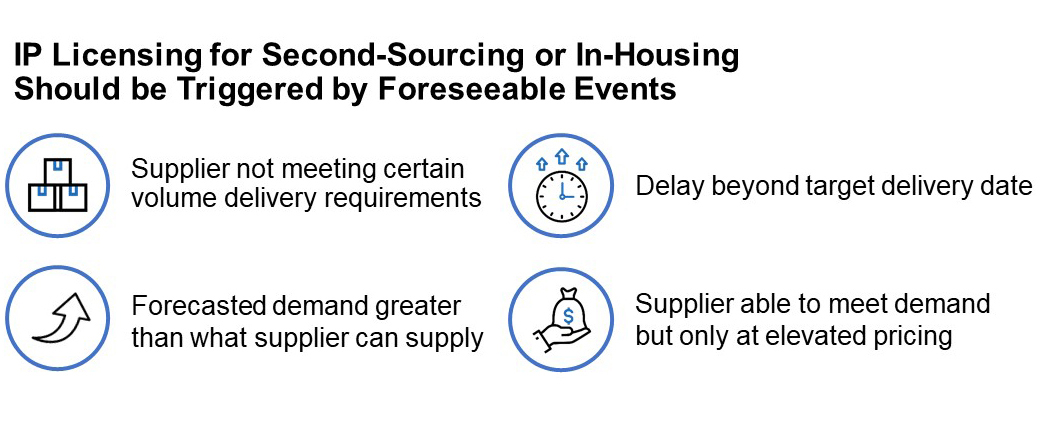

Many conditions may trigger the activation of such licenses:

Customers pushing for conditional licenses from suppliers need to understand that they will come at a cost. For example, the supplier may demand a royalty payment from the customer for each component that is not produced by them. In instances where the customer has agreed to purchase a component from a supplier and the supplier is prevented from supplying the component to other customers (e.g., due to joint development between the supplier and the customer whereby the supplier can provide the component only to the partner/customer, etc.), the supplier may desire to have such restrictions lifted if the customer is permitted to second-source or in-house the component. Alternatively, suppliers may desire to take their (higher cost) goods to the open market in exchange for the customer being able to second-source or in-house the component. Mutual upfront agreement, however, will reduce uncertainty for both parties and avoid hastened and contentious discussions later when, by definition, product delivery is at stake.

Enforceability

Like many terms in a supply agreement, a conditional license that permits a company to utilize the IP of a supplier should be clear. The contract should expressly recite the terms of the license, including at a minimum providing for the following: (a) how the license activates (e.g., for convenience, only upon certain triggers, etc.), (b) exactly what IP the company can use, (c) how long the license is permitted, and (d) costs associated with the use. The terms should also expressly recite exactly what information, if any, the supplier needs to provide as part of a technology transfer to allow the customer to manufacture the product.

A lack of specificity in the agreement can make it unclear what exactly the supplier needs to provide as part of the IP transfer.2 Without sufficient contractual terms, courts may be wary to force IP transfers that could undermine the supplier’s IP rights (e.g., the disclosure of trade secrets such as proprietary manufacturing processes).3 In most cases, the preferred remedy for enforcing the technology transfer contemplated by a conditional license in a supply agreement will be a preliminary mandatory injunction. Among judicial remedies, only such an injunction can deliver the timely transfer necessary to avoid significant supply line disruption. But mandatory (requiring affirmative acts of performance) as opposed to prohibitory (prohibiting certain conduct) injunctive relief is particularly difficult to obtain on a preliminary basis.4 For this reason, it is especially important that the terms of a conditional license in a supply agreement be set forth in explicit detail. As an example, such a provision could state that “the supplier licenses patents A and B, engineering drawing C, CAD model D, and bill of materials E for a period of X [days/months/years] at a royalty rate of Y for each component Z manufactured or caused to be manufactured by the customer.” To enhance clarity and specificity, one option could be to include each document that would be considered part of the IP transfer in a transfer packet as an exhibit to the supply agreement.

An alternative approach that might enable the parties to avoid the delay and uncertainty associated with court action would be to establish an intellectual property escrow. Such an escrow would require an agreement clearly establishing the material and information to be placed in escrow, and very specific language defining the circumstances and documentation required to authorize an escrow agent to release the escrowed matter to the customer. The escrow agreement could also include language obligating the supplier to provide to the escrow agent any new IP required to perform the supply agreement as it is put into practice. Policing the supplier’s compliance with such an updating obligation would be difficult; the customer may have to rely to some degree on the supplier’s good faith in disclosing new IP developments as they occur. As a result, even a carefully drafted escrow agreement may not completely displace the need for judicial remedies.

Conclusion

Regardless of the terms, establishing the right to access supplier IP at the outset of a business relationship adds clarity for both sides. Properly utilized, it can eliminate tense discussions in the event that unexpected supply chain disruptions arise.

Subscribe to the Supply Chain Disruption Series

To help you navigate these uncharted territories in supply chain, we invite you to subscribe to Foley’s Supply Chain Disruption series by clicking here.

1 While this article discusses patents and know-how, almost all of its contents apply equally to confidential information, copyrights (e.g., in software code, in engineering drawings, in computer-aided-design models, etc.), and trade secrets to the extent the supplier shares such confidential information, copyrightable material, and trade secrets with the customer (e.g., via a non-disclosure agreement (NDA)).

2 See Inovia Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. GeneOne Life Science Inc., Case No. 20-06554, 2020 WL 5047283, at *37–39 (Pa. Com. Pl. Aug. 25, 2020). Noting that the difficulty in determining exactly what is required of the supplier to properly effectuate a technology transfer in compliance with the supply agreement causes problems with administering and enforcing a preliminary injunction requiring performance.

3 See Id. at *24–26. Noting that when considering a request for a preliminary injunction, courts routinely balance harms to both parties and do not disregard harm to the supplier on the ground that such harm is the consequence of compliance with a provision of a contract.

4 See id. at *10 Noting that the courts have engaged in greater scrutiny of mandatory injunctions and declared that they should be issued more sparingly than injunctions that are merely prohibitory; plaintiffs must show a clear right to relief to obtain a mandatory injunction.