In a long-awaited decision in Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Iancu (argued December 2017), the Federal Circuit held that the USPTO improperly imposed a Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) deduction for “applicant delay” during a period when the applicant “could have done nothing to advance prosecution.” The PTA deduction at issue was charged under 37 CFR § 1.703(c)(8) for an Information Disclosure Statement (IDS) filed after a Request for Continued Examination (RCE) had been filed, but the decision could have broader implications.

I first wrote about PTA deductions in the post-RCE period in this article, after the USPTO started charging PTA deductions for post-RCE submissions.

The Patent Term Adjustment Statute

The PTA statute at issue is 35 USC § 154(b)(2)(C), which provides for a deduction from any PTA award “equal to the period of time during which the applicant failed to engage in reasonable efforts to conclude prosecution of the application.” The statute also expressly delegates to the USPTO the authority to “prescribe regulations establishing the circumstances that constitute a failure of an applicant to engage in reasonable efforts to conclude processing or examination of an application.”

The Patent Term Adjustment Rules

The USPTO exercised its delegated authority in 37 CFR § 1.704(c), which sets forth a number of circumstances deemed to constitute “applicant delay” under the PTA statute. Since sometime after the Federal Circuit decision in Novartis v. Lee, the USPTO has invoked 37 CFR § 1.704(c)(8) to charge applicant delay when the applicant files an IDS after having filed an RCE, but before the next Office Action or Notice of Allowance:

(8) Submission of a supplemental reply or other paper, other than a supplemental reply or other paper expressly requested by the examiner, after a reply has been filed, in which case the period of adjustment set forth in § 1.703 shall be reduced by the number of days, if any, beginning on the day after the date the initial reply was filed and ending on the date that the supplemental reply or other such paper was filed.

The PTA Deduction At Issue

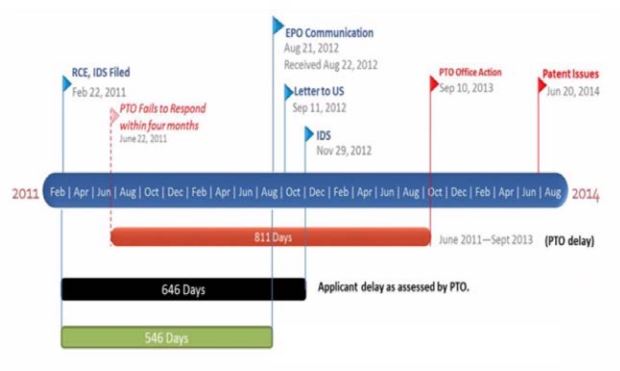

The PTA deduction at issue was charged for an IDS filed November 29, 2012 after an RCE filed February 22, 2011. The IDS submitted information cited in an Opposition filed August 21, 2012 in a related European application.

As illustrated by the black bar in this image from the Federal Circuit decision, the USPTO charged a period of applicant delay that ran from the date the RCE was filed until the date the IDS was filed. The red bar illustrates the USPTO delay in taking more than four months to issue an Office Action after the RCE was filed. The green bar illustrates the time period of most concern to the Federal Circuit.

Supernus challenged the PTA deduction in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. The district court upheld the PTA deduction based on the Federal Circuit decision in Gilead v. Lee, which upheld the USPTO’s application of 37 CFR § 1.704(c)(8) to an IDS filed after a response to a restriction requirement.

The Federal Circuit Decision

The Federal Circuit decision was authored by Judge Reyna and joined by Judges Dyk and Schall.

The Federal Circuit first explained why Gilead did not foreclose Supernus’s arguments:

In Gilead, this court held that the regulation “is a reasonable interpretation of the [PTA] statute” insofar as it includes “not only applicant conduct or behavior that result in actual delay, but also those having the potential to result in delay irrespective of whether such delay actually occurred.”

*****

The precise question in this case is whether the USPTO may reduce PTA by a period that exceeds the “time during which the applicant failed to engage in reasonable efforts to conclude prosecution.” 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(2)(C)(i). Gilead did not decide that question.

The Federal Circuit next applied the Chevron framework for reviewing an agency’s interpretation of a statute it administers. Unlike the issue presented in Gilead, the Federal Circuit determined that the statute directly addressed the issue here:

[T]he pertinent language of the PTA statute is plain, clear, and conclusive.

The court explained:

A plain reading of the statute shows that Congress imposed two limitations on the amount of time that the USPTO can use as applicant delay for purposes of reducing PTA. First, the statute expressly requires that any reduction to PTA be equal to the period of time during which an applicant fails to engage in reasonable efforts. Second, the statute expressly ties reduction of the PTA to the specific time period during which the applicant failed to engage in reasonable efforts.

The Federal Circuit reasoned:

PTA cannot be reduced by a period of time during which there is no identifiable effort in which the applicant could have engaged to conclude prosecution because such time would not be “equal to” and would instead exceed the time during which an applicant failed to engage in reasonable efforts.

Turning to the facts before it, the Federal Circuit noted that “that there was no action Supernus could have taken to advance prosecution” during the 546-day period illustrated by the green bar above, because the European opposition had not yet been filed.

According to the Federal Circuit:

Here, the USPTO’s interpretation of the statute would unfairly penalize applicants, fail to incentivize applicants not to delay, and fail to protect applicants’ full patent terms. The USPTO’s additional 546-day assessment as applicant delay is contrary to the plain meaning of the statute because … [it] is not equal to a period of time during which Supernus failed to engage in reasonable efforts to conclude prosecution.

The Federal Circuit therefore reversed the district court decision, and remanded for further proceedings consistent with its opinion.

How To Treat Post-RCE/Post-Response IDS Submissions

While the Federal Circuit held that there could be no applicant delay before the European opposition was filed, it did not address at what point in time the applicant could have been determined to have “failed to engage in reasonable efforts to conclude prosecution” consistent with the PTA statute. While not invoked here, 37 CFR § 1.704(d) could provide a benchmark. As characterized in the Federal Circuit decision, that rule provides a 30 day “safe harbor” for filing an IDS citing information from a counterpart application without incurring a PTA deduction.

See this article on how the USPTO is addressing its inability to properly apply this rule when calculating PTA.

In view of 37 CFR § 1.704(d), if and when the USPTO exercises its authority to “prescribe regulations establishing the circumstances that constitute a failure of an applicant to engage in reasonable efforts …. ” consistent with this decision, applicants should be afforded at least 30 days before being subject to a PTA deduction.

Also, while the “delay” at issue in this case arose during the post-RCE period, similar issues could arise for IDSs filed after a response to an Office Action has been filed.