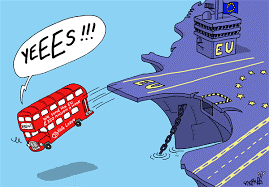

Four and One-Half Years! January 1, 2021 … at last … at long last as some might celebrate… or, as others might lament, a day which should have never come. Brexit is finally arriving. Four and one-half years have passed since the June 23, 2016 United Kingdom (“UK”) referendum on UK membership in the European Union (“EU”). On that day, UK voters narrowly chose to end its 40+ years’ membership in the EU. Since 2016, there has been intense debate, political pressure, economic dislocation, rancor and wild claims of impending doom or success.

Now, the UK’s exit from the EU has arrived. It leaves the EU pursuant to a trade and cooperation agreement in principle that was signed late on Christmas Eve, December 24, 2020.1 Some rejoiced and others decried the UK’s exit. Supporters say it will free the UK to chart its own destiny, to rid themselves of Brussels regulation and to seek free trade agreements with countries around the world, like the United States. Others say that the UK outside the EU trade bloc will flounder.2

In any event, as the EU has observed somewhat coolly of the UK decision, “this was its choice.”3 This “Brexit’s Exit” recalls the words of then Prime Minister Winston Churchill who said in 1942 after a decisive Second World War allied victory in North Africa that this was an historic time – “the end of the beginning,” he said. Some might, though less optimistically, say as well about Brexit that it may be “the beginning of the end.”4

This article will review briefly the run-up to the new agreement and important changes that the UK/EU agreement will mean for the UK and the EU, including some significant challenges that lie ahead.5 For both the EU and the UK, but particularly for the UK, January 1, 2021 is a time of reckoning after years of uncertainty, economic regression and political strife.6 This article concludes that while much is positive (particularly a semblance of certainty going forward in sectors like manufacturing) and that while both the UK and the EU made significant compromises and concessions to protect important (economic, political and cultural) interests, the jury is still very much out.

Years of Division and Turmoil

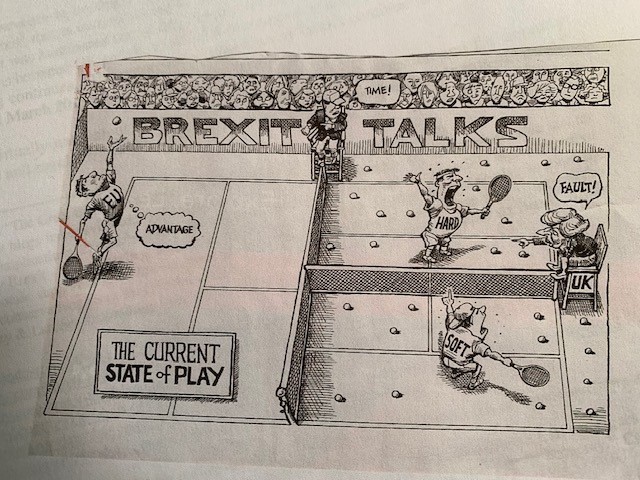

Brexit was approved in June 2016 by a razor-thin majority. Proponents touted Brexit as a chance for the UK to seek its own destiny through independence and self-determination. They argued that Brexit will mean renewed preeminence (economically, culturally, politically) that had been diminished (or in the minds of extreme Brexiters destroyed) by Brussels’ regulatory constraints and obligations of membership in the EU. Proponents of continued EU membership countered that the UK had benefitted enormously (economically, politically and culturally) through membership in the largest and, in their view, one of the most successful union of national shared destinies ever created.7 While the EU stood-by watching with increasing concern and seemingly all of the advantages, Brexit divided the UK practically down the middle – hard and soft – as if they were playing or negotiating their future against each other.

The years after the 2016 referendum were filled in the UK with acrimony. Rhetorical predictions of disaster grew more and more strident. For many, particularly those in manufacturing industries like motor vehicles, the political divisions, inaction, investment uncertainty and the potential for a UK hard exit from the EU (with concomitant high tariffs, quotas and technical barriers to trade) were for many the stuff of continuing nightmares.8

On the other hand, for many hardline Brexiters, the long-cherished goals of independence and self-determination were deemed well worth any potential economic downside.

Yet, for many, the negative economic consequences of Brexit for the UK were already apparent – reduced competitiveness, escalating unemployment, brain drain and capital flight. The UK manufacturing sector, particularly the motor vehicle industry, was devastated. In 2018, motor vehicle industry investment dropped 46.5% from 2017 and vehicle production fell to its lowest level in many years. Manufacturers were voting with their feet taking their production and their jobs with them. Companies like Honda, Nissan, JRL and Michelin idled, shuttered or ceased investment in UK production facilities. Many realigned their supply and distribution infrastructures outside the UK, often in one of the remaining 27 EU member states. The UK’s prior long-standing credibility as a safe and secure place for business and investment was severely undercut by the economic uncertainty precipitated by the continuing Brexit crisis.9 The industry’s fears of the nightmare consequences of a no-deal Brexit were to surface yet again in 2020 during the final rounds of negotiations when UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson repeated warned his colleagues to prepare for a no-deal Brexit.10

A New Beginning: The December 23, 2020 Trade and Cooperation Agreement

That said, however, the December 23, 2020 EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (“TCA”) setting forth the terms of the future EU/UK economic relationships appears to have moved dramatically away from a no-deal Brexit and industry’s nightmare scenarios.11 Important interest of both sides were protected and significant compromises by each side were made.12 However, it is plain that there are big changes in the UK/EU relationship. The UK will no longer be a part of the EU single market and customs union. The EU and the UK will exist as two separate markets, with two distinct regulatory and legal schemes. Free movement of goods, services, people and capital between the EU and the UK ends. As the EU describes it, vis-à-vis the EU, “the UK is a third country.13

However, the TCA reflects important compromises that may well militate some of the draconian consequences that would have occurred in the absence of an exit deal.14 The TCA provides that there will be no tariffs or quota on trade in all goods between the EU and the UK, including politically sensitive agricultural, fishery and motor vehicle products which would have faced substantial tariffs under the WTO rates that would have been otherwise applicable.15 This should be particularly important for the manufacturing sector. Further, there are comprehensive principles and procedures that relate to rules of origin, product conformity to applicable EU/UK regulatory standards16 and customs procedures.17 On customs procedures, while there will be increased paperwork and formalities for both sides, they have been simplified through mutual recognition procedures and waivers.

Major contentious issues of state aid, standards, fisheries and technical barriers to trade were addressed and a series of measures are proposed to protect each side. The goal was a level playing field.18 For the UK, it was a non-starter that the European Court of Justice would retain jurisdiction to determine and control how disputes on issues like state aids, standards and technical barriers to trade were resolved. For the EU, it was unacceptable that UK firms might seek to achieve any commercial advantage by lowering product standards (e.g., labor, environmental, product quality, etc.) or by granting UK industries unfair state aid subsidies (e.g., tax benefits or other forms of subsidies). To achieve this desired level playing field, the EU/UK agreed that these kinds of concerns or disputes (jurisdictional or commercial) were to be resolved through a dispute settlement procedure. Claims of unfair treatment by either side were to be arbitrated with the goal of finding a common ground on which to resolve the claimed unfair trade practice. Failing a mutually agreeable resolution, the aggrieved side could impose tariffs to mitigate the effects of the alleged unfair trade practice.19

One clear and significant gap in the TCA, with potential enormous economic implications, relates to financial services. Though the text of the TCA runs more 1250 pages, there is scant mention of financial services – a major part of the UK economy. Obviously, free movement of services (including financial services) now enters a period of uncertainty until a separate agreement is reached to cover such services. Indeed, it had already been decided, when the TCA was under consideration, that the UK’s relationship with the EU on issues of financial services would be the subject of a separate agreement to be negotiated in the future.20 Suffice to say, for now, the TCA makes clear that UK service suppliers in the EU must comply with local rules in each of the 27 member states and will no longer benefit from the country-of-origin principle, mutual recognition or passporting rights for financial services. Their option after the TCA takes effect is to establish themselves as an entity authorized by the laws of an EU member state in the EU in order to offer services within and across the national borders of the EU27.21 Negotiation of an agreement on financial services remains a significant challenge and is vital to the UK economy if it is to rebound from the recent erosion that has followed, rightly or wrongly, from Brexit.

Conclusion

After four and one-half years, is Brexit the end of the beginning or the beginning of the end? Is it a chance to regain cherished independence and self-determination as some claim? Is it, in an increasingly global and interdependent world, a cruel and counterproductive hoax destined to marginalize the UK? Can the UK successfully negotiate free trade agreements with other countries like the United States, Canada and Australia? Can the UK, as the EU has just done, negotiate an agreement with China to ease investment restrictions? In the short term, as noted above, the UK economy is likely to shrink by more than 4%.

On balance, however, the Brexit agreement on future EU/UK trade and cooperation reflects significant choices and compromises made to protect perceived economic and political interests of both sides. Whether those choices and compromises will bear fruit remains to be seen. Time will tell, of course, of the wisdom of UK’s choice.22

———————————————————–

1 On October 17, 2019, the UK and the EU signed a “withdrawal agreement” and a non-binding political declaration setting forth their future political, economic, strategic, etc. relationships and setting the stage for this December 24, 2020 agreement in principle on their post-Brexit trade and commercial relationships. It is subject to approval by the UK and EU parliaments and the EU Council. The UK Parliament gave its prompt approval after the Christmas holidays. EU approvals are expected in January 2021. As such, the EU has agreed to provisional application of the agreement until the end of February 2021. See, The Wall Street Journal said that this “Brexit Deal Brings Clarity But Not Closure.” (December 26-27, 2020). The Washington Post said “Britain avoids a Brexit disaster, but divorce from Europe will still hurt” (December 30, 2020).

2 The UK government’s own estimates predict the UK economy will shrink more than 4% in the short term. See Wall Street Journal, “The Brexit deal Brings Clarity But Not Closure,” supra.

3 See https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_2531.

4 Prime Minister Johnson actually said, “Brexit is not an end but a beginning and the responsibility now rests with all of us to make the best use of the power that we have regained.” See “U.K., EU part ways on day 1 of Brexit” Wall Street Journal (January 2-3, 2021).

5 This is the ninth in a series of ongoing blog posts on Brexit by Howard Fogt. Links to earlier articles are at https://www.autoindustrylawblog.com and https://www.foley.com/Brexit.

6 Since the 2016 voter referendum on UK membership there have been frequent changes at 10 Downing Street along with virtually constant bickering and recriminations.

7 After centuries of war, rivalry and economic insularity, the EU’s goal of free movement of goods, capital services and people had achieved significant benefits. Many in the UK, however, remained skeptical.

8 See “Tied to Europe, Britain’s Car Industry is Vulnerable after Brexit,” The New York Times (December 16, 2016); “Toyota Demands Clarity over Brexit,” The New York Times (October 25, 2017). The uncertainty continued to the very end. See “Bust-ups and brinksmanship: inside story of how the Brexit deal was done,” The Guardian (December 24, 2020).

9 In those dark days, there were dire predictions of doom and gloom. John Allen, then President of the Confederation of British Industry (“CBI”) said in an address to his CBI colleagues that “… a no-deal Brexit would be a nightmare scenario … which would be a wrecking ball for our economy.” CNBC (November 18, 2018).

10 See “Bust-ups and brinksmanship: inside story of how the Brexit deal was done,” The Guardian (December 24, 2020).

11 A comprehensive summary of the provisions of the TCA was issued by the European Commission. It details the terms of the comprehensive agreements relating to 1) trade; 2) connectivity; 3) citizens security; and 4) a governance framework for cooperation. See https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_2531.

12 There are some significant issues that were not included in the trade and cooperation agreement. For example, the agreement does not deal with cooperation on foreign policy, external security and defense, even if those areas of cooperation were originally foreseen in the 2016 political declaration. Further, the TCA does not deal with other important issues – equivalences for financial services, data protection and sanitary/phytosanitary regimes. These are left for another day, as had been specifically foreseen for some time regarding financial services, an issue of great significance for the UK economy.

13 See the EU statement on the TCA, n. 2 supra, which references the UK in somewhat sterile terms as “third country” presumably at least to distance itself from the UK and to underscore, albeit coolly, that the UK is no longer a part of the EU free trade zone.

14 See “5 Takeaways from the Post-Brexit Trade Deal,” The New York Times (December 24, 2020).

15 Under WTO rules, tariffs above 40% would be levied on certain meat and dairy products, 25% for canned fish, and 10% for motor vehicles exported either way between the EU and the UK.

16 UK exporters can self-certify compliance with EU regulatory standards for certain products and there will be regulatory regimes to make conformance easier for pharmaceuticals and motor vehicles.

17 Generally self-certification and cumulation is intended to reduce red-tape and other trade-inhibiting restraints. Nevertheless, there is now a significant shortage of trained customs inspectors to perform the border checks that will, in fact, be required. Trade will be slowed.

18 On the contentious and emotion-charged issue of fisheries, the EU and the UK long and often bitter rivalry in this sector was settled, at least for the moment, by the EU agreeing to reduce its current fishing quota in UK waters by 25% (as opposed to the 80% reduction that the UK had originally demanded). But this reduction will be phased in over a five and one=half year period (as opposed to the 10-year phase in period which the EU had originally demanded).

19 Suffice to say, while this dispute settlement procedural remedy for resolving disputes on unfair trade practices is a potentially useful tool and is not without precedent, it would appear to give significant incentive to the aggrieved party to impose tariffs and economic leverage to press its commercial advantage. One must assume that as both the EU and the UK remain members of the WTO that there will be some vehicle to address abuse of this power.

20 See “The City of London does not know what Brexit will mean,” The Economist (December 28, 2020).

21 In fact, many firms in the UK financial services industry, large and small, have already taken those steps.

22 Will Brexit talks ever end? Interestingly, the TCA provides for reviewing some trade terms after five years. See “The looming questions the Brexit deal did not answer,” The Washington Post (January 2, 2021).