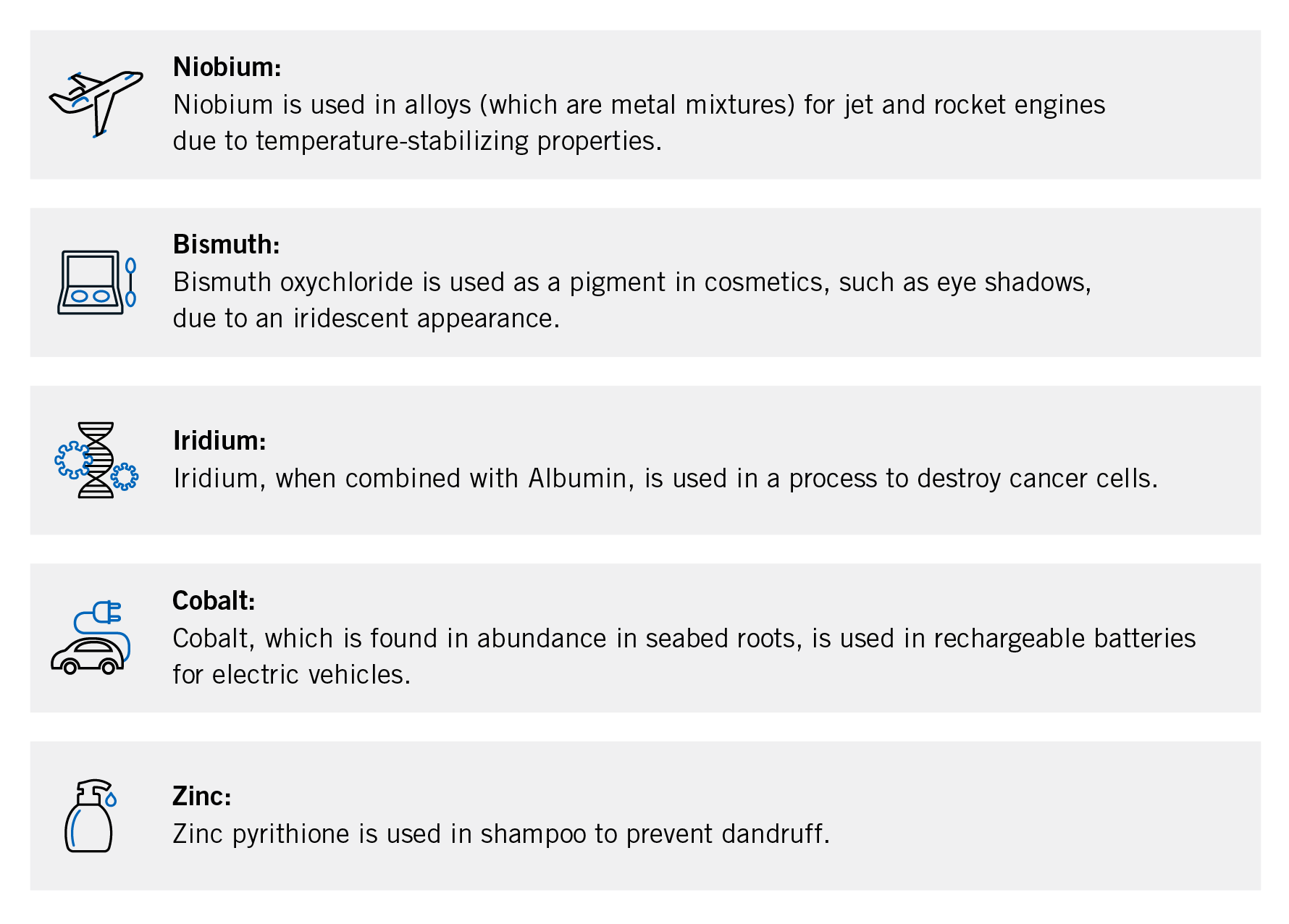

Critical minerals, which include rare earth minerals, are generally defined as minerals that are important to supply chains, but difficult to mine and ship due to scarcity, geopolitical issues, trade policy, or a combination of the three. The U.S. Department of the Interior identified 35 critical minerals that (1) are “essential to the economic and national security of the United States,” (2) have supply chains that are “vulnerable to disruption,” and (3) serve “an essential function in the manufacturing of a product, the absence of which would have significant consequences for our economy or our national security.”1 The list of critical minerals includes familiar minerals like aluminum, tungsten, and tin;2 minerals critical to electrification like lithium and cobalt; minerals critical to manufacturing like magnesium, manganese, niobium, and vanadium; and minerals used for nuclear fuel like uranium. Companies use these critical minerals to make mobile phones, airplanes, advanced electronics, wind turbines, electric cars, solar panels, and electricity generation and transmission systems. They are crucial for innovation, economic growth, and national security. Demand for critical minerals is increasing in the United States and worldwide as countries seek clean energy alternatives.

The United States relies heavily on imports to satisfy its demand for critical minerals, and importers rely heavily on China for critical and rare earth elements. The Trump administration took steps to increase domestic production of critical minerals with bipartisan support, and the Biden administration continues to recognize U.S. reliance on imports from China.3 In his February 24, 2021 executive order (“EO”) on supply chain resiliency, President Biden directed the U.S. Secretary of Defense to identify risks in the supply chain for critical minerals and create policy recommendations to address those risks.4

Challenges Associated with Critical Mineral Sourcing

Critical mineral supply chains face major challenges. First, the lack of an industry certification standard makes it difficult to compare performance from one mine to another. Second, critical minerals are fungible (e.g., there is no way to differentiate one kilogram of cesium from another). Third, some companies may illegally mine rare earth minerals and sell them into the supply chain without any paper trail. Finally, a number of countries impose restrictions and regulations on critical minerals.

In the United States, the federal government heavily regulates critical mineral sourcing. In June, 2021, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (“CBP”) issued a Withhold Release Order (“WRO”) against Hoshine Silicon Industry Co. Ltd. (“Hoshine”), a company located in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (“XUAR”).5 The WRO instructed personnel at all U.S. ports of entry to detain shipments containing silica-based products made by Hoshine and its subsidiaries.6 This WRO applies not only to silica-based products made by Hoshine and its subsidiaries but also to materials and goods derived from or produced using those silica-based products.7 When the CBP issues a WRO pursuant to 19 U.S.C. §1307, the importer of record bears the burden to provide documentation that the withheld product was not produced or mined using forced labor.8 Given the complexity and opacity of Chinese supply chains, as well as paper recordkeeping practices where records can be lost, altered, or falsified, companies may find this standard difficult to meet, even in instances where the product is in fact free from forced labor.

On December 23, 2021, President Biden signed the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (the “UFLPA”), which requires the CBP to block all shipments of goods from the XUAR because they are presumed to have been made with forced labor. The presumption is rebuttable, but at the time of this publication, there is no consensus within industry or government on the types of evidence that can be presented to the CPB to rebut the presumption of forced labor. And the stakes are high – when the CBP finds that an importer successfully rebutted the presumption – it must issue a report to Congress stating as much. Fortunately for U.S. importers, the Department of Homeland Security has asked the public to provide input on the types of due diligence, supply chain tracing and supply chain management measures that importers can use to prevent the import of goods made with forced labor and the nature and types of evidence that importers can provide to rebut the presumption of forced labor in products from the XUAR.9

Blockchain Technology for Critical Minerals

Blockchain tracing technology facilitates improved management of geopolitical risk and supply chain uncertainty because records held on blockchain are digital, trusted, and time-stamped.

Digitized Records

With blockchain, importers no longer need to ask their suppliers, who must in turn ask their own suppliers, for paper documentation of the origin of critical minerals. The paper process is labor intensive, time consuming, and sometimes not sufficient to satisfy import requirements. Blockchain would allow importers – and the CBP – at the time of import, to differentiate between products subject to, and products not subject to, the UFLPA or a WRO, without referencing a paper trail.

Trusted Records

Blockchain technology provides secure, immutable records that allow importers to confirm accountability from their global suppliers and to rebut the presumption under the UFLPA that the supplier used forced labor to mine the metals. Blockchain technology could prove particularly useful in this context because miners in the XUAR do not necessarily export these rare earth metals directly. For example, the XUAR is an important source of rare earth metals used in consumer electronics and aviation, and products made elsewhere in China may incorporate rare earth metals mined in the XUAR. Further, some rare earth metals enter the global supply chain indirectly after export to other countries. If the CBP were to target rare earth metals mined in the XUAR as part of the UFLPA, blockchain technology would make clear to U.S. importers (and the CPB) whether an engine manufactured in Thailand contains rare earth metals mined in the XUAR.

Time-stamped Records

Because blockchain transactions are time-stamped and may be recorded at every stage of the supply chain, blockchain further helps suppliers to act in real time, ensuring supply chain integrity from start to finish.

Implementing Blockchain for Critical Mineral Tracing

Blockchain technology has arrived at a fortuitous time for U.S. importers and provides a powerful tool for industries struggling with supply chain traceability issues. The government of Australia, the world’s second largest producer of critical minerals10 after China, recognizes as much. In July 2021, the Australian government awarded a $3 million AU pilot project to the blockchain provider, Everledger.11 The pilot project will use Everledger’s blockchain technology to create a “digital certification” for critical minerals throughout the supply chain – from extraction to processing to export to global markets.12 Australia perceives that companies throughout the critical minerals supply chain could use the technology to simplify traceability, lower costs, and better comply with supply chain traceability regulations in their home countries. The Australian government also hopes this “digital certification” will increase the demand for Australian minerals in global markets while simplifying the process and lowering costs.

Similarly, Teck, one of Canada’s leading mining companies with operations in Canada, the U.S., Chile, and Peru13 has identified potential benefits blockchain could provide to the mining industry and announced a partnership with DLT Labs to harness blockchain technology to trace the critical mineral germanium from the source to the customer.14 Germanium is used for fiber optic cables and high-speed computer chips and circuitry; Germanium is considered a necessary ingredient for modern-day communications platforms and low-carbon economies.15 Teck and DLT Labs plan to use the new blockchain solution to go beyond recording data relating to responsible sourcing; they also plan to use it to track environmental, social and governance practices along the supply chain, including greenhouse gas emissions and product certifications.16

Given the United States government’s increased use of trade policy to promote national security objectives, and given the unreliable nature of manual documentation for supply chain traceability purposes, critical mineral sourcing is ripe for the use of blockchain.

————————————————————————————————————————————————

1 Interior Releases 2018’s Final List of 35 Minerals Deemed Critical to U.S. National Security and the Economy, Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey (May 18, 2018).

2 The U.S. and E.U. designated tungsten, tin, and tantalum as “conflict minerals,” a term that is not synonymous with critical minerals. Conflict minerals are minerals mined in parts of the world where conflict affects the mining and trading of the minerals. U.S. and E.U. law requires companies that import these minerals to certify that they were mined outside of a conflict zone or certified as “conflict-free.”

3 See U.S. Department of Commerce Announces Section 232 Investigation into the Effect of Imports of Neodymium Magnets on U.S. National Security, U.S. Department of Commerce (September 24, 2021).

4 E.O. 14017.

5 See The Department of Homeland Security Issues Withhold Release Order on Silica-Based Products Made by Forced Labor in Xinjiang, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (June 24, 2021); Walsh, Michael J. et al., Forced Labor Sanctions in the Solar Industry – What You Need to Know, Foley & Ladner LLP (June 25, 2021).

6 Id.

7 Id.

8 Forced Labor, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, (last retrieved December 28, 2021).

9 Walsh, Michael J. et al., Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act – Comment Period Open until March 10, 2022, Foley & Ladner LLP (January 27, 2022).

10 Critical Minerals, Global Business & Talent Attraction Taskforce Australia, (last retrieved September 28, 2021); Daly, Tom, China Becomes World’s Biggest Importer of Rare Earths: Analysts, Reuters (March 13, 2019).

11 Press Release: Everledger Wins Major Australian Government Critical Minerals Blockchain Pilot Project, Everledger (July 12, 2021).

12 Id.

13 About, Teck (last retrieved February 22, 2022).

14 Teck and DLT Partner to Pilot Traceability for Critical Minerals with Blockchain, Teck (January 20, 2022).

15 Id.

16 Id.