In Biogen International GmbH v. Banner Life Sciences LLC, a panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) held that the scope of a patent term restoration under 35 U.S.C. §156 only includes the active ingredient of an approved product (in this case, dimethyl fumarate or DMF, the active ingredient in Biogen’s Tecfidera®) or an ester or salt of that active ingredient.

In affirming the judgment of the district court, the CAFC agreed that the compound used in Banner’s accused product (methyl hydrogen fumarate, also known as monomethyl fumarate or MMF) is neither the active ingredient nor an ester or salt of that active ingredient.

Thus, the CAFC found no infringement by Banner of the portion of the term of the patent-in-suit, which was extended due to “delays” associated with the process of obtaining regulatory approval to market Biogen’s Tecfidera®.

We would like to exercise our literary license and go back in time—to revise history and offer up a “reverse” hypothetical scenario in which Biogen, or any drug innovator similarly situated, makes a different choice early on in its drug development program—altering the result in this case and delivering a win for Biogen.

In describing the reverse hypothetical scenario, we hope to draw attention, albeit in hindsight, to the benefits of a close collaboration between an innovator’s clinical and legal advisers in deciding, among two or more choices, which compound to designate as the company’s lead drug candidate.

Claim 1, the sole independent claim of the patent-in-suit, US 7,619,001 B2, is reproduced below:

- A method of treating multiple sclerosis comprising administering, to a patient in need of treatment for multiple sclerosis, an amount of a pharmaceutical preparation effective for treating multiple sclerosis, the pharmaceutical preparation comprising at least one excipient or at least one carrier or at least one combination thereof; and dimethyl fumarate (DMF), methyl hydrogen fumarate (MMF), or a combination thereof. (abbreviations added)

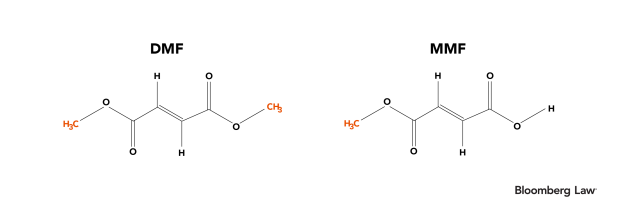

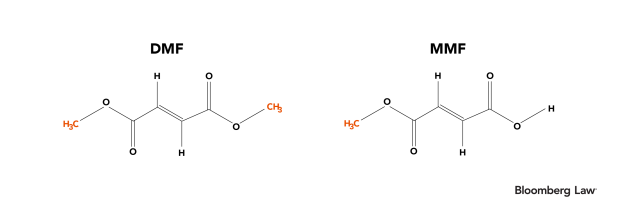

Additionally, the chemical structures of DMF and MMF are depicted below:

At the risk of telegraphing this article’s punchline, we note that even a cursory examination of their chemical structures reveals that DMF is a methyl ester of MMF.

The patent-in-suit was originally scheduled to expire as of April 1, 2018. Its term was extended under the provisions of Section 156 by 811 days, and the extended portion of the term is set to expire on June 20. Referring to Section 156, the CAFC wrote:

- Subsection (b) limits the scope of the patent extension to ‘any use approved for the product,’ and further, for method of treatment patents, to uses also ‘claimed by the patent.’ § 156(b)(2). Critically, for the purposes of this appeal, subsection (f) defines ‘product’ as ‘the active ingredient of … a new drug … including any salt or ester of the active ingredient.’ § 156(f)(2)(A).

Moreover, the CAFC added that:

- ‘Active ingredient’ is a term of art, defined by the FDA as ‘any component that is intended to furnish pharmacological activity or other direct effect,’ 21 C.F.R. §210.3(b)(7), and it ‘must be present in the drug product when administered.’ (citation omitted)

DMF had been under investigational development (IND 73061) in the U.S. for the treatment of multiple sclerosis since 2006. By the time Biogen submitted its new drug application (NDA) to the FDA in February 2012, which received approval from the FDA in March 2013, the patent-in-suit and the subject matter recited in its claims had granted long before (November 2009).

As mentioned above, the claims covered DMF, MMF, or a combination thereof. We can only speculate as to the reasons (e.g., better safety profile, better oral availability, stability, ease of manufacture) why Biogen decided to move ahead with the approval process in favor of DMF (over MMF, DMF’s only active metabolite).

It is apparent, however, that MMF was also available, having been present in a combination of fumarate esters found in Fumaderm®, a drug product approved in Germany in 1994 for the treatment of psoriasis. We assume, for the purposes of this reverse hypothetical scenario, that MMF was also not previously approved for marketing by the FDA and would have been categorized as a new chemical entity (NCE). If our assumption is correct, and all other things being equal, Biogen could have chosen to move forward with MMF as its lead candidate.

If Biogen had chosen MMF as its lead candidate and ultimately won MMF’s approval for marketing by the FDA, then Biogen could still have selected the patent-in-suit for patent term restoration under Section 156 because the patent-in-suit covers the approved use of DMF, MMF, or a combination thereof.

If Biogen had chosen MMF as the active ingredient in Tecfidera®, it would have enjoyed the extended portion of the term of the patent-in-suit free from generic competition because the extended portion of the term would have covered the use of MMF as the active ingredient, “including any salt or ester of the active ingredient” under §156(f)(2)(A). Pfizer Inc. v. Dr. Reddy’s Labs. Ltd., 359 F.3d 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2004).

Accordingly, in the reverse hypothetical scenario, if Banner had presented DMF as the active ingredient in the accused product, Biogen would have prevailed because DMF is an ester of the active ingredient, MMF. Indeed, Banner could have chosen any ester of MMF and Biogen would have still won.

If Biogen had chosen MMF as its lead candidate, Biogen v. Banner would never even have happened.