Software Companies Sued For Patent Infringement May Seek Speedy Dismissals

Patent infringement litigation can be expensive, last multiple years, and be a huge distraction for a company’s efforts in the marketplace. While fighting an infringement accusation through trial to final judgement can be emotionally satisfying, an early exit to litigation may save significant resources for a defendant. The recent case DataWidget, LLC v. The Rocket Science Group, LLC provides an example of strategies software companies may use to obtain early dismissals of patent infringement cases lacking a sufficient factual basis.

Background

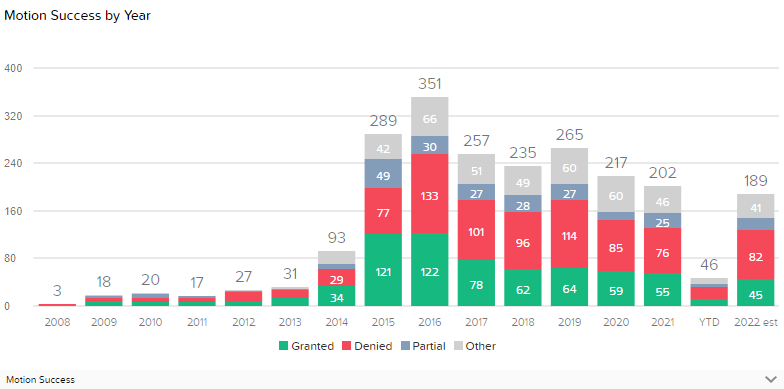

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and substantive patent law provide Defendants in patent cases a variety of protections against unfounded lawsuits, though these protections may have limited application. For example, Federal Rule 11 allows for dismissal of a suit and sanctions where plaintiffs failed to conduct adequate pre-complaint investigations; but as seen in Hoffmann-LaRoche, Inc. v. Invamed, Inc., Plaintiffs could avoid sanctions by asking accused Defendants to explain the operation of products that could not be determined from publicly available information. In 2014, the Supreme Court ruled in Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l that patent claims directed to a computer‐implemented scheme for mitigating “settlement risk” were not patent eligible under 35 U.S.C. §101, but instead covered a patent‐ineligible abstract idea, and that generic computer implementation failed to transform that abstract idea into a patent‐eligible invention. Subsequent to Alice, motions to dismiss based on allegedly unpatentable subject matter have been frequently used in software related cases, and the filing of such motions soared from 31 motions in 2013 to over 350 motions in 2016.

As outlined in our previous analysis, a year later in 2015 the bare bones form patent complaint of Form 18 was abrogated and Plaintiffs were required to plead enough factual content to allow a court to draw the reasonable inference that the defendant is liable for the misconduct alleged. Two years later, in 2017, the Supreme Court’s decision in TC Heartland LLC v. Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC clarified that for purposes of patent venue, a corporation “resides” only in its state of incorporation, and not just any forum where it is subject to personal jurisdiction, thus limiting he venues in which companies could be sued. The DataWidget case, however, identifies an additional strategy Defendants may use to avoid suits even if it is sued in an appropriate venue and Plaintiff has complied with Rule 11 obligations by seeking an explanation from the targeted Defendant concerning operation of the accused system.

New Developments

In DataWidget, the Plaintiff asserted it was the owner of a patent relating to a system for “selling individually-tailored customer-specific data subsets on a third-party website using a data seller widget.” Plaintiff contacted the Defendant prior to filing suit to inquire how it integrated data from data sellers into its webpage, but the Defendant never responded. Undeterred, and potentially protected from Rule 11 sanctions by having made an inquiry of Defendant concerning operation of the accused system, Plaintiff filed a patent infringement lawsuit, admitting in the complaint that its infringement allegations were based on a series of assumptions that a non-party software developer created software used by Defendant that performs the functions claimed by Plaintiff’s patent. When challenged on Defendant’s motion to dismiss, Plaintiff asserted that it adequately pleaded (1) ownership of the patent, (2) the infringer’s name, (3) a citation to the infringed patent, (4) the infringing activity, and (5) citations to federal patent law, which under the abrogated Form 18 would have been sufficient to plead patent infringement.

The Court found that Form 18 required “little more than a conclusory statement alleging that the defendant infringed on the claimant’s patent,” and that under current pleading standards, Plaintiff “must show how the defendant plausibly infringes by alleging some facts connecting the allegedly infringing product to the claim elements.” The complaint only speculated how the accused system worked, and the Court found that Plaintiff cannot properly allege infringement without factual allegations showing how Defendant’s system actually purportedly practiced the patent claims limitations. While the Court recognized that Plaintiff could “do little more than speculate when it has no insight into” Defendant’s operations without discovery, the Court refused to let the case go forward because “allowing this case to proceed based on assumptions would impermissibly lower the pleading standard such that any patent holder can pursue claims, and force a defendant to incur the time and costs of litigation, simply because another product resembles its own.” Thus, the Court dismissed the complaint and found that Plaintiff is not “entitled to discovery to determine whether it has a claim in the first place.”

Conclusion

The DataWidget case is of special importance to software companies whose products cannot be reverse engineered by potential patent plaintiffs. Sometimes cooperating with a patentee to explain that infringement could not possibly occur has resolved lawsuits, but cooperation does not guarantee that a dispute will be avoided. After DataWidget, software companies have additional incentive not to cooperate with potential Plaintiffs, as the admission from a Plaintiff that it does not have a factual basis for asserting infringement may lead to early dismissals of cases.