Alice Patent Eligibility Analysis Divergence Before USPTO and District Court

The Mayo/Alice[1] framework for determining subject matter eligibility of patents under 35 U.S.C. §101 has long since antagonized both patent prosecutors and litigators alike, causing significant uncertainty in the realm of software-based technology and innovation. Adding to this uncertainty, the Patent Office applies two-step Alice analysis differently than the district courts, sometimes leading to conflicting determinations from patent examiners and judges reviewing the same claims. Indeed, while the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (“MPEP”) and other United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) guidance on application of the Alice analysis ostensibly interprets and applies Alice and its progeny, the approach made by patent examiners under current guidelines allows for claims to be deemed to be directed to eligible subject matter so long as the judicial exception is “integrated into a practical application” at which point the claims are deemed not directed to a judicial exception.

Practitioners should appreciate the nuances between the Alice analysis in prosecution and litigation in order to obtain issued patents that will also withstand scrutiny when an opposing party rigorously challenges the claims under the Alice framework in the district court.

Alice Before the Courts

The two-step Mayo/Alice analysis first articulated by the U.S. Supreme Court is well-known to patent litigators. The court must first “determine whether the claims at issue are directed to a patent-ineligible concept” relating to the judicial exceptions of a law of nature, natural phenomenon, or an abstract idea (i.e., “Step One”).[2] If Step One is satisfied, then the court must “consider the elements of each claim both individually and ‘as an ordered combination’ to determine whether the additional elements ‘transform the nature of the claim’ into a patent-eligible application” (i.e., Step Two).[3] Step Two of the Alice analysis constitutes a search for an “inventive concept” which is an element or combination of elements in the claim “sufficient to ensure that the patent in practice amounts to significantly more than a patent upon the [ineligible concept] itself.”[4]

In short, courts only apply the above two steps: (1) determine whether the claims are directed to a patent-ineligible concept; if yes, (2) determine whether the claim elements, in combination, recite an inventive concept amounting to significantly more than a patent upon the ineligible concept itself. These two steps comprise the inquiry for subject matter eligibility before the courts. It should be noted that courts have rarely found inventive concepts as part of their Step Two analysis, so the determination on Step One largely controls the inquiry.

Alice Before the Patent Office

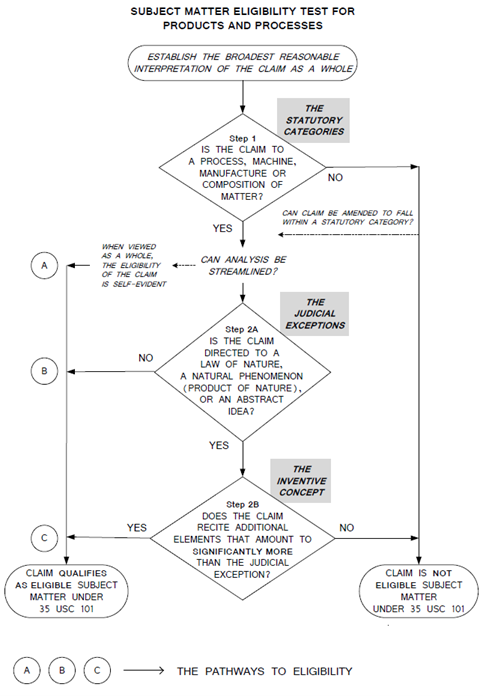

MPEP §2106 provides Patent Office guidance on how examiners address the Alice subject matter eligibility analysis during prosecution. The following flow chart is meant to aid examiners addressing these issues.

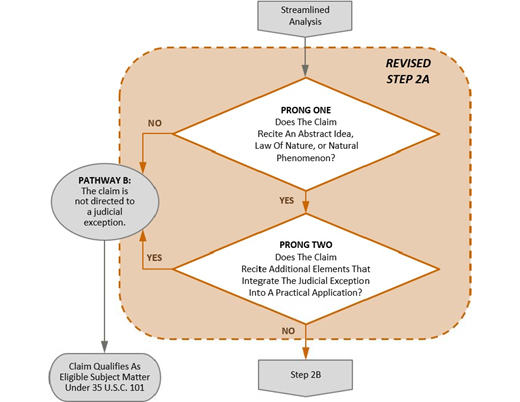

As can be seen, Step 2A corresponds to Step One of Alice applied by district courts, and Step 2B corresponds to Step Two. However, unlike in the Alice analysis conducted by district court judges, the USPTO has further subdivided step one of Alice (e.g., Step 2A) into two distinct inquiries as shown below[5]:

The second prong of Step 2A asks examiners to determine whether claims that recite a judicial exception nonetheless recite additional elements that integrate the judicial exception into a “practical application.” In addition, the USPTO issued its 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance in the Federal Register (“2019 Guidance”), which includes the following guidance with respect to Prong Two of Step 2A of the Patent Office process:

Examiners evaluate integration into a practical application by: (a) Identifying whether there are any additional elements recited in the claim beyond the judicial exception(s); and (b) evaluating those additional elements individually and in combination to determine whether they integrate the exception into a practical application, using one or more of the considerations laid out by the Supreme Court and the Federal Circuit, for example those listed below. While some of the considerations listed below were discussed in prior guidance in the context of Step 2B, evaluating them in revised Step 2A promotes early and efficient resolution of patent eligibility, and increases certainty and reliability. Examiners should note, however, that revised Step 2A specifically excludes consideration of whether the additional elements represent well-understood, routine, conventional activity. Instead, analysis of well-understood, routine, conventional activity is done in Step 2B. Accordingly, in revised Step 2A examiners should ensure that they give weight to all additional elements, whether or not they are conventional, when evaluating whether a judicial exception has been integrated into a practical application.[6]

Alice Analysis Side-By-Side

When laid out side-by-side, it is clear that the MPEP’s “integration into a practical application” approach in Prong Two of Step 2A goes beyond the approach taken by district courts by incorporating aspects of Step Two of Alice into Step One.

| U.S. Supreme Court Two-Step Alice Approach | USPTO/MPEP Alice Approach |

| Step One: Determine whether the claims directed to a patent-ineligible concept; and if yes; Step Two: Determine whether the claim elements, in combination, recite an inventive concept amounting to significantly more than a patent upon the ineligible concept itself. | Step 2A Prong One: Determine whether the claim recites a patent-ineligible concept; and if yes Step 2A Prong Two: Determine whether the claim recites additional elements that integrate the patent-ineligible concept into a practical application; and if no Step 2B: Determine whether the claim recites additional elements that amount to significantly more than the ineligible concept itself. |

“Integrated into a Practical Application”

Critically, at Prong Two of Step 2A, examiners analyze whether claims integrate a judicial exception into a practical application and may not strictly determine whether the specific additional elements represent well-understood, routine, conventional activity. For example, the 2019 Guidance specifically instructs “in revised Step 2A examiners should ensure that they give weight to all additional elements, whether or not they are conventional, when evaluating whether a judicial exception has been integrated into a practical application.”[7] But once an examiner decides that the claims integrate the judicial exception into a practical application, the claims are deemed to be patent-eligible without needing to proceed to Step 2B, which some argue would otherwise discount the conventional additional elements (similar to the Court’s application of Alice Step Two).

This approach may lead to scenarios where an examiner determines patent claims are eligible under Alice because the claims integrate a practical application via elements that may otherwise be conventional, and then those same claims are later determined to be ineligible by a district court that separately accounts for the conventional aspects in Alice Step Two and does not consider the “integration” step that is applied during examination in the Patent Office.

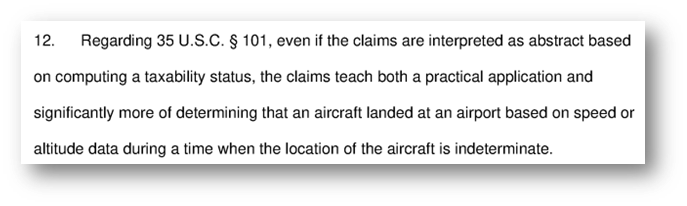

Regarding case law on this very issue, Aviation Capital Partners, LLC v. SH Advisors, LLC[8] is illustrative. That case involved a patent infringement action asserting three claims of U.S. Patent No. 10,956,988, which issued on March 23, 2021, relating to determining the taxability status of aircraft. During prosecution of the patent, there was a rejection based on subject matter eligibility under Alice, but after a claim amendment, the examiner determined the claims were patent-eligible because they integrated the abstract idea into a practical application.[9]

The USPTO patent examiner addressed the Alice analysis during prosecution. In litigation, a district court judge at the early motion to dismiss stage stated that it was not affording deference to the examiner’s approach: “the determination of taxability status is also an abstract idea — as the Patent Office recognized…I give no weight to the Patent Office’s overall determination that the patent was eligible.”[10] There was no discussion by the court about the “practical application” in the Alice Step One analysis. Instead, the court addressed the patent owner plaintiff’s arguments about the examiner’s statements about the “practical application” in Alice Step Two, stating that “[d]espite having a practical application, the claims of the patent offer no new insights or improvements for implementing their abstract idea…I again give no weight to the conclusions of the PTO.”[11]

While this decision is currently on appeal, it demonstrates that a district court judge may not agree with the USPTO’s rationale for withdrawing §101 rejections based on the “practical application” approach. Further, even where there is a practical application, some district courts may expect more of “practical application” in Prong Two of Step 2A than a given USPTO examiner in a given case. That said, other court decisions have shown more deference to examiners’ §101 determinations that claims integrate a judicial exception into a practical application at the motion to dismiss stage.[12]

USPTO Doubles Down in 2024 Guidance on Patent Eligibility for AI Inventions

Effective July 17, 2024, the USPTO issued new AI subject matter eligibility guidance.[13] While meant to specifically address inventions related to AI technology, the USPTO doubled down on the inquiry at Step 2A Prong Two relating to asking “whether the claimed invention as a whole integrates the recited judicial exception into a practical application.” Moreover, the updated 2024 Guidance for AI inventions reiterates that “[a]t Step 2A Prong Two or Step 2B, there is no requirement for evidence to support a finding that the exception is not integrated into a practical application or that the additional elements do not amount to significantly more than the exception unless the examiner asserts that additional limitations are well-understood, routine, conventional activities in Step 2B.” These new guidelines do not comment on the varying applications of Alice and its progeny before the USPTO examiners and district court judges.

Bridging the Gap

While the 2019 Guidance and updated 2024 Guidance for AI inventions include citations to case law for prong two of Step 2A, none of the cases cited discuss the first step of the Alice analysis with the “integration of a practical application” approach explicitly — that is, the cited cases have not directly used that language. In fact, the cases provided by the 2019 Guidance arrived at such language from disparate §101 jurisprudence, including cases that addressed the practical application analysis at Alice Step Two relating to searching for the inventive concept.[14]

To be sure, the MPEP does indicate that the analysis of integration into a practical application is appropriate at Step 2B. For example, the MPEP states that for “a claim reciting a judicial exception to be eligible, the additional elements (if any) in the claim must ‘transform the nature of the claim’ into a patent-eligible application of the judicial exception, either at Prong Two or in Step 2B.”[15]

Yet, the MPEP encourages disposition of §101 issues earlier in the eligibility analysis such that the determination of whether a claim is integrated into a practical application will often occur before getting to Step 2B. For example, MPEP § 2106.06(b) allows examiners to utilize a “streamlined eligibility” analysis. The streamlined eligibility analysis is used when the eligibility of the claim is self-evident, e.g., because the claim clearly improves a technology or computer functionality. If there is such an improvement, the claim qualifies as eligible subject matter under § 101 without needing to undergo further analysis. Prong Two of Step 2A encourages examiners to address the integration into a practical application at Step One of Alice instead of Step Two but, as discussed, does so without accounting for whether the additional elements of the claim are conventional.

Some court decisions do not appear to necessarily subdivide the first step of the Alice analysis in the same way. While there is some overlap between the two steps in Alice, judges have not expressly decided a patent claim was not directed to a judicial exception because it was “integrated into a practical application” at Alice Step One.

While patent examiners are generally expected to follow MPEP and other guidance issued by the USPTO over Federal Circuit decisions, neither are binding on the courts, and some district court decisions do not show deference to USPTO examiner’s § 101 analysis., Moreover, the Federal Circuit has stated that §101 case law controls rather than the 2019 Guidance.[16] The recently updated 2024 Guidance for AI inventions is silent regarding this tension. It is entirely possible the Federal Circuit takes the opportunity in the Aviation Capital Partners appeal to speak more directly on what could be considered a split between the USPTO and district courts on §101 eligibility analysis.

Alternatively, new proposed legislation in the Patent Eligibility Restoration Act may remove uncertainties in the application of §101 before the USPTO and district courts.

Conclusion

Patent applicants facing §101 rejections may want to consider strategies for establishing eligibility that take into account not only MPEP and other USPTO guidance, but also how district courts are approaching similar issues. This could mean providing some analysis beyond on the USPTO’s Step 2A, Prong Two analysis. Depending on the circumstances, such strategies might include creating a record pointing out how any “additional elements” are not routine and conventional and pursuing claims of varying scope within the same patent or across a family. Such a record may be useful in later litigation.

[1] Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc., 566 U.S. 66 (2012); Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 573 U.S. 208 (2014).

[2] Alice, 573 U.S. at 217-18; Mayo, 566 U.S. at 72, 77-79.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] MPEP §2106.04.

[6] 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance, 84 Fed. Reg. 50 (Jan. 7, 2019).

[7] 84 Fed. Reg. 50 (Jan. 7, 2019).

[8] Civil Action No. 22-1556-RGA, 2023 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 145104 (D. Del. Aug. 18, 2023).

[9] U.S. Patent 10,956,988 File History, February 18, 2021 Notice of Allowance, p. 5.

[10] 2023 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 145104 at *11.

[11] Id., at *13.

[12] See e.g., Rich Media Club LLC v. Duration Media LLC, No. CV-22-02086-PHX-JJT, 2023 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 120102, at *13-14 (D. Ariz. July 11, 2023) (denying motion to dismiss on §101 grounds, in part because in the Notice of Allowance for the asserted patent, the examiner concluded “[t]he amendment in combination with other limitations form an ordered combination and integrated practical application. 101 withdrawn.”).

[13] 2024 Guidance Update on Patent Subject Matter Eligibility, Including on Artificial Intelligence, 89 Fed. Reg. 137 (July 2024).

[14] See e.g., 84 Fed. Reg. 50 (Jan. 7, 2019) (citing BASCOM Glob. Internet Servs., Inc. v. AT&T Mobility LLC, 827 F.3d 1341, 1352 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (concluding that claims could be eligible under Alice Step Two if an alleged inventive concept can be found in the ordered combination of limitations that “transform the abstract idea…into a particular, practical application of that abstract idea.”); CLS Bank Int’l v. Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd., 717 F.3d 1269, 1315 (Fed. Cir. 2013) (Moore, J., joined by Rader, C.J., and Linn and O’Malley, JJ., dissenting in part) (“The key question is thus whether a claim recites a sufficiently concrete and practical application of an abstract idea to qualify as patent-eligible. Prometheus instructs us to answer this question by determining whether a process involving a natural law or abstract idea also contains an ‘inventive concept.”), aff’d, 573 U.S. 208 (2014).

[15] MPEP §2106.04 (emphasis added) (citations omitted).

[16] See e.g., cxLoyalty, Inc. v. Maritz Holdings Inc., 986 F.3d 1367, 1375 n.1 (Fed. Cir. 2021) (“Throughout its Final Written Decision, the Board repeatedly referred to the United States Patent and Trademark Office’s 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance, 84 Fed. Reg. 50 (Jan. 7, 2019). We note that this guidance is not, itself, the law of patent eligibility, does not carry the force of law, and is not binding on our patent eligibility analysis. And to the extent the guidance contradicts or does not fully accord with our caselaw, it is our caselaw, and the Supreme Court precedent it is based upon, that must control.”) (citations omitted).